Last week we had a visitor at school. In fact we had four. But rather than that warm, fuzzy feeling you feel when your uncle, auntie and two cousins pop round for some mulled wine and a mince pie in the run-up to Christmas, the whole school drew a sharp intake of breath and waited for the pain: Ofsted were coming.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m not one of those teachers who spirals into a whirlwind of panic, staying at school until 9pm and winding everyone else up with me. I know that I’m doing the things that Ofsted wants to see all year round, but not necessarily in every lesson all the time. You will understand my relief when the HMI gave me my feedback on her thirty minute observation: “that was definitely a 1”.

Outstanding & MFL

Now I don’t claim to be an expert on what makes every lesson Outstanding (this is teaching’s Holy Grail and, frankly, I think Monty Python would have trouble finding it even if we set them loose in the corridors of the DfE!). But I do know why my lesson was Outstanding, and I do know how other languages teachers can get there too. Here are my six simple steps to outstanding (note the consonance – catchy, right?).

Step 1: Engagement

No, my role is not to entertain – it is to help students to learn; but we all know that they learn better when they are enjoying what they’re doing. I don’t necessarily mean have ‘fun’ – you can enjoy something without having fun. The key is using learning activities that the students like doing: mine like using mini whiteboards, so I use them; they like doing silly voices when we use choral repetition, so we do; they like watching me do silly (and sometimes random!) actions to go with the words we’re practising, so I do them.

This sounds like a no-brainer, but how many of us have been drawn into the attitude you can hear repeated in every staffroom of the country?: “kids these days need to learn to sit quietly and listen,” “I’m not a clown,” “I don’t have time to play games, they need to learn”. Most of this is rubbish; the workplace nowadays is a much more vibrant place than it was before, and communication is key. In the UK, many of our students will be going on to work in service industries or in communicative jobs, such as those found in call centres. How are we preparing them to communicate if we make them sit at a desk and listen or write for an hour?

In my Ofsted-observed lesson, I used a range of activities my students enjoy to introduce book genres in French: choral repetition with actions for phonics revision; mini whiteboards for introducing the vocabulary using multiple choice and a Quiz-Quiz-Trade game to practise the phrases.

For ideas on the kinds of activities you can use, check out my post on The Kagan Method as a startpoint, or just get creative! It’s amazing what you can do with a bag full of dice…

Step 2: Sequencing

I was horrified at a GTP Subject Mentors’ conference last term when I discovered that most of my fellow mentors, all experienced MFL teachers, had never heard of PPP: Presentation, Practice, Production.

Lots of us will do these in some form or another without realising. The problem is that most of us don’t spend time on the largest ‘P’ – Practice, and most of us don’t sequence the stages strictly enough. Let me explain…

Imagine you are teaching students to use the comparative. You explain to the how to use plus…que, moins…que and aussi…que. You maybe do some mini whiteboard work. Then you want them to write their own comparative sentences. NO!

The problem here is that you haven’t allowed them to practise the structure enough, and by practise I basically mean repeat. Now I’m not suggesting that you spend a whole lesson repeating the phrase Monsieur M est plus cool que Monsieur S (my favourite model!) but you need to leave the structure wholly visible while the students spend most of the lesson ‘practising’ it – trying it out – with the support of the words on the board. They could be building sentences with dice, doing a RallyCoach activity (see the Kagan post) or playing a card game where they have to repeat simple comparative phrases (such as Kagan’s Quiz-Quiz-Trade or rosaespanola‘s ‘Cheat‘ card game), but the point is that they are using the structure over and over again without having to remember how it works – it’s the repetition that internalises the language. Once this stage is fully complete (after an hour, a week or even a term, depending on the structure) then get to the final P – Production.

In my lesson, the activities were clearly sequenced from Presentation – where I presented the vocabulary and had the students repeat, to Practise – where I used a Quiz-Quiz-Trade activity to get students repeating and remembering the words.

Step 3: AfL

Since its introduction into teaching, AfL has been the obsession of CPD leaders, SLTs and Ofsted inspectors alike, and rightly so; being able to ask students to assess their own learning and checking their understanding to inform your teaching is such an invaluable tool, and it’s so simple to do!

At my current school, students have green, amber and orange pages in their planner. Once I had done the choral repetition stages of my lesson and the practice activities, I asked students how well they felt they knew the vocabulary:

Using Assessment for Learning to check pupils’ confidence with new vocabulary is an invaluable tool.

Obviously the wording needs to be changed according to the activity you’ve been doing and what you’re leading on to, but the above descriptors worked perfectly for the next activity, and the next of my six steps…

Step 4: Differentiation

This is likely to be the least popular of my steps; the staffroom cynics claim that differentiation is “too time-consuming” and that it doesn’t help students, since “they all have to sit exactly the same exam”. There is some truth in these points, but only because people have lost sight of what differentiation is for, and how to use it.

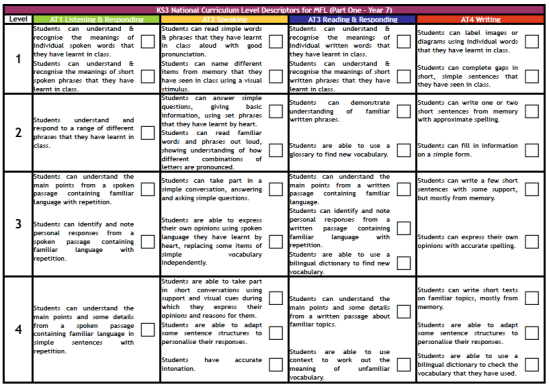

Firstly, differentiation isn’t supposed to be permanent: it should be used to push students on to the next level that is appropriate for them, with the aim of slowly weaning them off it for different skills and activities so that they can all pass that exam. I differentiate my activities for each skill (listening, speaking, reading & writing) according to pupils’ attainment grade for that individual skill and gradate the activities throughout the term so that they can finally complete a given task in that skill with no support.

Secondly, yes it can be time consuming, but we’re not talking about hours of work, and it’s work that you can keep forever! I tend to start with the same reading or listening text, and then use (a lot!) of copy and paste to modify the activities, ranging from those where students note down the information required independently to multiple-choice activities with tick-boxes.

In the lesson seen by the HMI, I had prepared two different worksheets for the same listening text: one green and one orange. Those students who had shown a green card took the green sheet, those who had shown the orange card took the orange one. Simples!

This differentiated listening activity linked on perfectly from the AfL traffic lighting I did just before… and all just as the inspector walked into my room!

Step 5: Simplicity

As an NQT, I had an awful problem: for some reason, I got it into my head that when I was being observed, every lesson had to be groundbreaking, earth-shattering, innovative and, above all, COMPLICATED. I was clearly suffering from a prolonged stroke.

Whenever I was observed I tried to get students to make inhuman leaps in their learning, I had umpteen worksheets for each differentiated group and I made the lessons unmanageable. I even once got a 3! Sad times.

So my advice is, keep it simple – be realistic and don’t panic just because Ofsted are in. The best lessons are the ones that work, and those lessons are usually the simplest of all.

My ‘Outstanding’ lesson was painfully simple. By the end the students were able to ask the question Qu’est-ce que tu lis en ce moment and answer it with an opinion. Not groundbreaking, not earth-shattering, but in the words of the inspector, the pupils made “excellent progress”. Job done.

Step 6: Consistency

I have one request of anyone that reads this post: please, please, PLEASE do not wait until Ofsted announce their imminent arrival before putting any of the above tips into practice – it won’t work.

My heart truly sinks when teachers tell me that they replan their lessons for Ofsted – you shouldn’t need to. It isn’t hard to introduce one piece of differentiation a week (at first) and a few engaging activities, right from the start of the year. Remember – Ofsted inspectors, as much as we may hate them, aren’t stupid – they’ll be able to tell if what they’re observing is a show for them, and if they suspect it is, they’ll ask the students, who will be more than happy to dob you in!

So, don’t wait until Auntie Ofsted is knocking at your door – make your lessons Ofsted proof NOW!

Update! Here is the PowerPoint presentation with the sequence of activities I used for this lesson: T1 Year 8 – 9. Qu’est-ce que tu lis